This chapter of Groothuis’ Christian Apologetics covers the objection that all roads lead to God.

The Blind Men and the Elephant

The famous “elephant and the blind men” parable is introduced and, later in the chapter, dismantled. The contradictory claims of differing religions are more like this: They say conflicting things about the same body parts. Ultimate reality cannot be both impersonal and personal. Our problem cannot be both a) we’re ignorant of our divinity/nothingness, and b) we’ve lost touch with our Creator. Our spiritual freedom cannot be both a) secured by grace demonstrated on the cross, and b) secured by knowledge of our own divinity/nothingness. And it is just “assumed” that there is this “whole elephant” they are all talking about–the very “essence” this parable claims every religion only captures partially. How is the parable maker able to capture this essence in whole, in order to formulate this parable, when all the world’s religions have failed to capture it? No religion thinks they are the blind man. To suggest the elephant exists is to cease to be the blind man. Contradictions cannot be reconciled.

Groothuis defines religion as “a set of beliefs that attempts to explain the nature of the sacred and how humans can become in harmony with it.” So this chapter does not assert that atheism is a religion/worldview. That whole issue is avoided altogether. I like how Tim Keller defined worldview and tackled this issue in The Reason for God.

But I like how Groothuis fleshes out that religions all grapple with what our problem is, and how to solve it. Where they differ is what the exact problem is, and what the exact solution is.

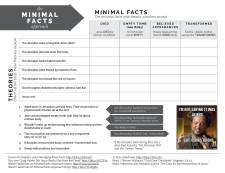

Christianity views God as a Trinity and recognizes a Creator-creature duality, that we are in the image of God but have lost touch with him, and that the solution is to accept the Way back to him: grace demonstrated on the cross. Nondualistic Hinduism believes all is Brahman/divine, that all duality is illusory–the real reality is the self is indistinguishable from Absolute Self, and the solution to our uneasiness is to recognize all of that. Buddhism believes the real reality is Nirvana–absence of self/desire, the solution to our suffering. These conflicting core beliefs about the same parts of the elephant cannot be reconciled.

John Hick recognizes that this dismantles perennialism. Instead, he proposes that none of the religions have got at the elephant (he calls it the Real), though they all try. The Real exists, but we cannot get at it, through divine revelation or philosophy or otherwise. Ultimate reality is ineffable. (Problem: Isn’t saying that it exists and explains the world’s religions a form of getting at it? How does it explain them, if nothing can be said about it?–that’s like saying, “This death is explained by the fact that I have no idea who or what caused it.”)

I don’t like Groothuis’ criticism involving exclusive disjunction, because Hick already said–no religion gets at the Real. The exclusive disjunction objection only applies to perennialism, which Hick denies. Hick would likely affirm the Real needs to be either/or. What he denies is that we can know which the Real is. Maybe I’m wrong about that, because Hick says, “None of these descriptive terms apply literally to the unexperienceable reality that underlies that realm” — that does seem to go a bit further than “We just can’t know.” It seems to move closer to affirming non-duality/monism.

However, Groothuis has a good point that Hick cannot say, “The Real is neither personal nor nonpersonal,” while also saying, “The Real is neither good/loving, nor evil/hating.” If he is noncommittal on the personhood of the Real, then he has to commit to the fact that the Real is as able as a rock is to be good/loving/evil/hating. Also, Groothuis is right when he criticizes Hick for inconsistently saying that an impersonal (not good/evil) Real is behind this: When religions get it accidentally right and are in accidental alignment with the Real, they produce saints. Can an impersonal/ungood Real produce saints? If the Real is neither purposive, nor non-purposive, can it “produce” saints? Besides the inconsistency between impersonal/saints–Christianity says nonChristians can be good without God. They, too, are in God’s image and have his law written on their hearts (Romans 2:14-15).

While Hick’s hypothesis attempts a sort of pluralism, it is the highest form of exclusivism, because it essentially says everyone–everyone–is getting it wrong about the Real. No one is even able to get it right–the blind men were completely mistaken about the parts of the elephant they encountered.

Hick acknowledges: “If Jesus was literally God incarnate, and if it is by his death alone that men can be saved, and by their response to him alone that they can appropriate that salvation, then the only doorway to eternal life is Christian faith.” (Groothuis quoting Hick, p. 585 of “Christian Apologetics”)

What about those who have never heard?

The important words in this discussion are particularism versus inclusivism.

Does God send the ignorant to hell?

We should consider eight things while we address this question: 1. Don’t twist the Bible to be in line with other religions. 2. Remember the Great Commission of world evangelization (Matt. 28:18-20, Luke 24:44-47, Acts 1:8). 3. Look for the common ground that exists between Christianity and other religions (see Don Richardson’s “Eternity in Their Hearts”). 4. Make sure that common ground is not a perversion of the truth. 5. The Bible never says people will be judged according to what they could not have known (Romans 1:18-32, 2:14-15; Ps. 19:1-6). 6. None of us deserves redemption. 7. Whatever their fate, Jesus is the only one who redeems (Matt. 11:27, John 14:6, Acts 4:12, 1 Tim. 2:5). 8. Some will reject God and choose the alternative.

Groothuis offers possible solutions:

1. Their fate is in the hands of a just, holy and loving character, however he works it out.

2. Inclusivists believe salvation is possible for those who have never heard the gospel.

3. Particularists believe salvation is only possible for those who have knowledge of the gospel.

Some inclusivists put greater emphasis on faith than on the object of faith–this is unbiblical (Eph. 2:12, Acts 16:31). Other inclusivists require that a person realize the present object of their faith cannot save them and “cast themselves on the mercy of God.” This is more probable biblically (of the two), but Groothuis goes in for particularism (referring to Psalm 145:18, Acts 4:10-12, Romans 10:9-17).

He answers two objections to particularism by stating that 1) Cornelius, though considered a righteous Gentile, was not saved until after Peter told him about Christ (Acts 10), and 2) believers in the Hebrew Bible were saved (Galatians 3:8, Luke 2:29-32) who anticipated the Messiah in Scriptures and sacrifices.

Will more be lost than saved (Matthew 11:27, John 14:6, Matthew 22:1-44, Luke 14:15-24, Matthew 7:13-14)? Groothuis answers that those passages refer to Jews of Jesus’ day, and that Luke 13:22-30 shows this. Groothuis also points out the “many” in Matthew 20:28, Hebrews 2:10, Romans 5:19, Matthew 8:11 and the “multitude” in Revelation 7:14.

Groothuis also says:

1. Those who die very young are likely redeemed through God’s mercy.

2. Christians may always have been in the minority until very recently, but history is not over.

3. Humans are not the only messengers–angels can preach the gospel (Revelation14:6, Acts 9).

My thoughts: On number 7 above, it mentions it is Jesus’ name that saves. I would like to point out that his name is not a magic word. It is what Jesus stands for–that is what the OT saints anticipated. Jesus is God’s grace. It is God’s *grace* that saves. Jesus came to demonstrate it — it already existed, and his coming was planned before the world was made. So whether or not anyone hears, it is grace that saves. But God wants us to know and experience the reward of a relationship with our Creator and Savior–as soon as possible. Hence, the Great Commission.

No mention is made of verses that say we are only held accountable for the revelation (light) we have been given. See Acts 17:30 (barring this interpretation, which is false, though I love Piper), Luke 23:34/Acts 3:17, 1 Timothy 1:13, Matthew 11:21-24, Luke 12:48. If God can, in his mercy, make an exception for the young, he can make an exception for other examples of ignorance. If you have heard all the evidence of God’s demonstration of grace on the cross in Jesus, and you reject it–then you reject the light you have received, and you have made your choice. If you choose to remain in a state of “I don’t know”–that is the same as rejecting it.

There was a time when I rejected it, but he saved me out of it. I do consider it a time of ignorance. So, I have hope for you, if you are currently in a state of rejection, or “I don’t know.” And I know that God will do everything he can to get you to see the Point before he lets you choose the alternative. “The doors of hell are locked on the inside,” (C.S. Lewis). And there are many doors to hell.

More on my take on the problem of the unevangelized: Hell or Heaven: What about those who have never heard the gospel?

Book Discussion Index